REPORT

In the performance film piece Maihime, a gorilla with human skin appears on a monitor moving in sync with a dancer in the real world; in Kao1, different images fall and stick on a CG representation of the artist’s own face, like new skin. Shota Yamauchi examines the relationships between humans and technology, creating work that blurs the boundaries of the real and the virtual.

Yamauchi studied sculpture at university, and then film expression as a postgraduate. “I was born in a generation where games and animation were part of my everyday life. When I think back on the world I saw or conversations with my friends, virtual things never really seemed unreal. So when I enrolled in art university, I couldn’t connect western sculpture and painting with my own sense of reality. Of course, I understand it now, and even feel its attraction, but at the time I started producing my own work, my concept of reality lay in the games I had been familiar with since my childhood, or in scenery that built the virtual onto the real.”

Maihime and Kao1, mentioned above, feature strange textures (the feel of the surface or skin) that make the audience feel slightly uncomfortable. Yamauchi says that he began to work with these skins and textures after the Covid-19 pandemic began. “The biggest factor was that the method of communication came to be through screens. Communicating through filters in everyday life became more and more normal, and I wanted to explore the digital world for the sense of temperature and the feel of skin that texture should originally consist of.

The highlight of the work he is showing in this exhibition, for which he used StareReap2.5 technology, is also the detailed texture. The works include a two-dimensional piece with the gorilla from Maihime, the sculptural work from Kao1, and Waltz – three-dimensional paintings of human figures within clothes, questioning whether they are being embraced or imprisoned. There are also film pieces in the show. Yamauchi describes StareReap2.5 as “having a high affinity for expressing texture, which substantiates the image deep in the screen.” He continues confidently, “I think we expressed the sense of human skin and the feeling of the cloth in the dress that the gorilla wears in a way that feels quite real.”

The origin of the work is data created with computer graphics. So how does it convey a sense of reality? When asked about this, Yamauchi replies, “seeing as though you are touching, or touching something with your eyes – if you can do that, there might be a kind of reality. Having a sense of the real world is not necessarily the same as being real. I am sort of searching for the difference in my art. Reality is the feeling of a strong sensation that something is real, and it includes perceptual illusions and disconcertion. If that is true, then the sense of reality does not equate to actuality or truth. In fact, if a fictional thing is in a virtual space it might elicit a feeling of reality. To search for the source of reality is a mission for all people, not just for artists.”

With that in mind, it is interesting that the exhibited pieces, such as Waltz and Kao1, contain some elements of trompe-l'oeil: looking back over the long history of painting, there was a time when painters pursued not just the scenery in front of them, but also the illusion of, for example, a boat appearing to actually float on water. Yamauchi says that he admires painting, “especially the imagination of the expressionists and surrealists.” He continues, “Today’s technology is, I think, aiming at the substantiation of things that are on a screen, through various devices. In other words, not manipulating a world of images so that the audience ‘sees it in real life’, but to actually make something that is directly ‘experienced in real life’; to not just make it ‘feel like’ there is a smell, but to actually make the smell felt. Behind all of this is the idea that technological innovations that provide real, physical experiences are superior to those that work on the imagination. However, there is room left for the imagination in painting. I want to hold on to that.”

“In that sense, I feel we are living in a transition,” he says. “As VR devices are made thinner and become physicalized to the extent that we don’t feel their material presence, the distinction of what is ‘real’ or what is ‘reality’ may change. We are in the long process of this transition, and StareReap2.5 has value as one of the transitional technologies. It is not four-dimensional, but an expression in between two and three dimensions. It isn’t flat or sculptural. It is transitional. That is exactly why we, who are also in transition, are stirred by its expression.”

Yamauchi studied sculpture at university, and then film expression as a postgraduate. “I was born in a generation where games and animation were part of my everyday life. When I think back on the world I saw or conversations with my friends, virtual things never really seemed unreal. So when I enrolled in art university, I couldn’t connect western sculpture and painting with my own sense of reality. Of course, I understand it now, and even feel its attraction, but at the time I started producing my own work, my concept of reality lay in the games I had been familiar with since my childhood, or in scenery that built the virtual onto the real.”

Maihime and Kao1, mentioned above, feature strange textures (the feel of the surface or skin) that make the audience feel slightly uncomfortable. Yamauchi says that he began to work with these skins and textures after the Covid-19 pandemic began. “The biggest factor was that the method of communication came to be through screens. Communicating through filters in everyday life became more and more normal, and I wanted to explore the digital world for the sense of temperature and the feel of skin that texture should originally consist of.

The highlight of the work he is showing in this exhibition, for which he used StareReap2.5 technology, is also the detailed texture. The works include a two-dimensional piece with the gorilla from Maihime, the sculptural work from Kao1, and Waltz – three-dimensional paintings of human figures within clothes, questioning whether they are being embraced or imprisoned. There are also film pieces in the show. Yamauchi describes StareReap2.5 as “having a high affinity for expressing texture, which substantiates the image deep in the screen.” He continues confidently, “I think we expressed the sense of human skin and the feeling of the cloth in the dress that the gorilla wears in a way that feels quite real.”

The origin of the work is data created with computer graphics. So how does it convey a sense of reality? When asked about this, Yamauchi replies, “seeing as though you are touching, or touching something with your eyes – if you can do that, there might be a kind of reality. Having a sense of the real world is not necessarily the same as being real. I am sort of searching for the difference in my art. Reality is the feeling of a strong sensation that something is real, and it includes perceptual illusions and disconcertion. If that is true, then the sense of reality does not equate to actuality or truth. In fact, if a fictional thing is in a virtual space it might elicit a feeling of reality. To search for the source of reality is a mission for all people, not just for artists.”

With that in mind, it is interesting that the exhibited pieces, such as Waltz and Kao1, contain some elements of trompe-l'oeil: looking back over the long history of painting, there was a time when painters pursued not just the scenery in front of them, but also the illusion of, for example, a boat appearing to actually float on water. Yamauchi says that he admires painting, “especially the imagination of the expressionists and surrealists.” He continues, “Today’s technology is, I think, aiming at the substantiation of things that are on a screen, through various devices. In other words, not manipulating a world of images so that the audience ‘sees it in real life’, but to actually make something that is directly ‘experienced in real life’; to not just make it ‘feel like’ there is a smell, but to actually make the smell felt. Behind all of this is the idea that technological innovations that provide real, physical experiences are superior to those that work on the imagination. However, there is room left for the imagination in painting. I want to hold on to that.”

“In that sense, I feel we are living in a transition,” he says. “As VR devices are made thinner and become physicalized to the extent that we don’t feel their material presence, the distinction of what is ‘real’ or what is ‘reality’ may change. We are in the long process of this transition, and StareReap2.5 has value as one of the transitional technologies. It is not four-dimensional, but an expression in between two and three dimensions. It isn’t flat or sculptural. It is transitional. That is exactly why we, who are also in transition, are stirred by its expression.”

In the performance film piece Maihime, a gorilla with human skin appears on a monitor moving in sync with a dancer in the real world; in Kao1, different images fall and stick on a CG representation of the artist’s own face, like new skin. Shota Yamauchi examines the relationships between humans and technology, creating work that blurs the boundaries of the real and the virtual.

Yamauchi studied sculpture at university, and then film expression as a postgraduate. “I was born in a generation where games and animation were part of my everyday life. When I think back on the world I saw or conversations with my friends, virtual things never really seemed unreal. So when I enrolled in art university, I couldn’t connect western sculpture and painting with my own sense of reality. Of course, I understand it now, and even feel its attraction, but at the time I started producing my own work, my concept of reality lay in the games I had been familiar with since my childhood, or in scenery that built the virtual onto the real.”

Maihime and Kao1, mentioned above, feature strange textures (the feel of the surface or skin) that make the audience feel slightly uncomfortable. Yamauchi says that he began to work with these skins and textures after the Covid-19 pandemic began. “The biggest factor was that the method of communication came to be through screens. Communicating through filters in everyday life became more and more normal, and I wanted to explore the digital world for the sense of temperature and the feel of skin that texture should originally consist of.

The highlight of the work he is showing in this exhibition, for which he used StareReap2.5 technology, is also the detailed texture. The works include a two-dimensional piece with the gorilla from Maihime, the sculptural work from Kao1, and Waltz – three-dimensional paintings of human figures within clothes, questioning whether they are being embraced or imprisoned. There are also film pieces in the show. Yamauchi describes StareReap2.5 as “having a high affinity for expressing texture, which substantiates the image deep in the screen.” He continues confidently, “I think we expressed the sense of human skin and the feeling of the cloth in the dress that the gorilla wears in a way that feels quite real.”

The origin of the work is data created with computer graphics. So how does it convey a sense of reality? When asked about this, Yamauchi replies, “seeing as though you are touching, or touching something with your eyes – if you can do that, there might be a kind of reality. Having a sense of the real world is not necessarily the same as being real. I am sort of searching for the difference in my art. Reality is the feeling of a strong sensation that something is real, and it includes perceptual illusions and disconcertion. If that is true, then the sense of reality does not equate to actuality or truth. In fact, if a fictional thing is in a virtual space it might elicit a feeling of reality. To search for the source of reality is a mission for all people, not just for artists.”

With that in mind, it is interesting that the exhibited pieces, such as Waltz and Kao1, contain some elements of trompe-l'oeil: looking back over the long history of painting, there was a time when painters pursued not just the scenery in front of them, but also the illusion of, for example, a boat appearing to actually float on water. Yamauchi says that he admires painting, “especially the imagination of the expressionists and surrealists.” He continues, “Today’s technology is, I think, aiming at the substantiation of things that are on a screen, through various devices. In other words, not manipulating a world of images so that the audience ‘sees it in real life’, but to actually make something that is directly ‘experienced in real life’; to not just make it ‘feel like’ there is a smell, but to actually make the smell felt. Behind all of this is the idea that technological innovations that provide real, physical experiences are superior to those that work on the imagination. However, there is room left for the imagination in painting. I want to hold on to that.”

“In that sense, I feel we are living in a transition,” he says. “As VR devices are made thinner and become physicalized to the extent that we don’t feel their material presence, the distinction of what is ‘real’ or what is ‘reality’ may change. We are in the long process of this transition, and StareReap2.5 has value as one of the transitional technologies. It is not four-dimensional, but an expression in between two and three dimensions. It isn’t flat or sculptural. It is transitional. That is exactly why we, who are also in transition, are stirred by its expression.”

Yamauchi studied sculpture at university, and then film expression as a postgraduate. “I was born in a generation where games and animation were part of my everyday life. When I think back on the world I saw or conversations with my friends, virtual things never really seemed unreal. So when I enrolled in art university, I couldn’t connect western sculpture and painting with my own sense of reality. Of course, I understand it now, and even feel its attraction, but at the time I started producing my own work, my concept of reality lay in the games I had been familiar with since my childhood, or in scenery that built the virtual onto the real.”

Maihime and Kao1, mentioned above, feature strange textures (the feel of the surface or skin) that make the audience feel slightly uncomfortable. Yamauchi says that he began to work with these skins and textures after the Covid-19 pandemic began. “The biggest factor was that the method of communication came to be through screens. Communicating through filters in everyday life became more and more normal, and I wanted to explore the digital world for the sense of temperature and the feel of skin that texture should originally consist of.

The highlight of the work he is showing in this exhibition, for which he used StareReap2.5 technology, is also the detailed texture. The works include a two-dimensional piece with the gorilla from Maihime, the sculptural work from Kao1, and Waltz – three-dimensional paintings of human figures within clothes, questioning whether they are being embraced or imprisoned. There are also film pieces in the show. Yamauchi describes StareReap2.5 as “having a high affinity for expressing texture, which substantiates the image deep in the screen.” He continues confidently, “I think we expressed the sense of human skin and the feeling of the cloth in the dress that the gorilla wears in a way that feels quite real.”

The origin of the work is data created with computer graphics. So how does it convey a sense of reality? When asked about this, Yamauchi replies, “seeing as though you are touching, or touching something with your eyes – if you can do that, there might be a kind of reality. Having a sense of the real world is not necessarily the same as being real. I am sort of searching for the difference in my art. Reality is the feeling of a strong sensation that something is real, and it includes perceptual illusions and disconcertion. If that is true, then the sense of reality does not equate to actuality or truth. In fact, if a fictional thing is in a virtual space it might elicit a feeling of reality. To search for the source of reality is a mission for all people, not just for artists.”

With that in mind, it is interesting that the exhibited pieces, such as Waltz and Kao1, contain some elements of trompe-l'oeil: looking back over the long history of painting, there was a time when painters pursued not just the scenery in front of them, but also the illusion of, for example, a boat appearing to actually float on water. Yamauchi says that he admires painting, “especially the imagination of the expressionists and surrealists.” He continues, “Today’s technology is, I think, aiming at the substantiation of things that are on a screen, through various devices. In other words, not manipulating a world of images so that the audience ‘sees it in real life’, but to actually make something that is directly ‘experienced in real life’; to not just make it ‘feel like’ there is a smell, but to actually make the smell felt. Behind all of this is the idea that technological innovations that provide real, physical experiences are superior to those that work on the imagination. However, there is room left for the imagination in painting. I want to hold on to that.”

“In that sense, I feel we are living in a transition,” he says. “As VR devices are made thinner and become physicalized to the extent that we don’t feel their material presence, the distinction of what is ‘real’ or what is ‘reality’ may change. We are in the long process of this transition, and StareReap2.5 has value as one of the transitional technologies. It is not four-dimensional, but an expression in between two and three dimensions. It isn’t flat or sculptural. It is transitional. That is exactly why we, who are also in transition, are stirred by its expression.”

The artist Shota Yamauchi. The title ‘Ballet Mécanique’ is drawn from an experimental film by Fernand Léger and a music piece by Ryuichi Sakamoto. “The sound of ‘ballet’ as something physical and ‘mechanic’ as something mechanical echoed in my mind.”

The artist Shota Yamauchi. The title ‘Ballet Mécanique’ is drawn from an experimental film by Fernand Léger and a music piece by Ryuichi Sakamoto. “The sound of ‘ballet’ as something physical and ‘mechanic’ as something mechanical echoed in my mind.”

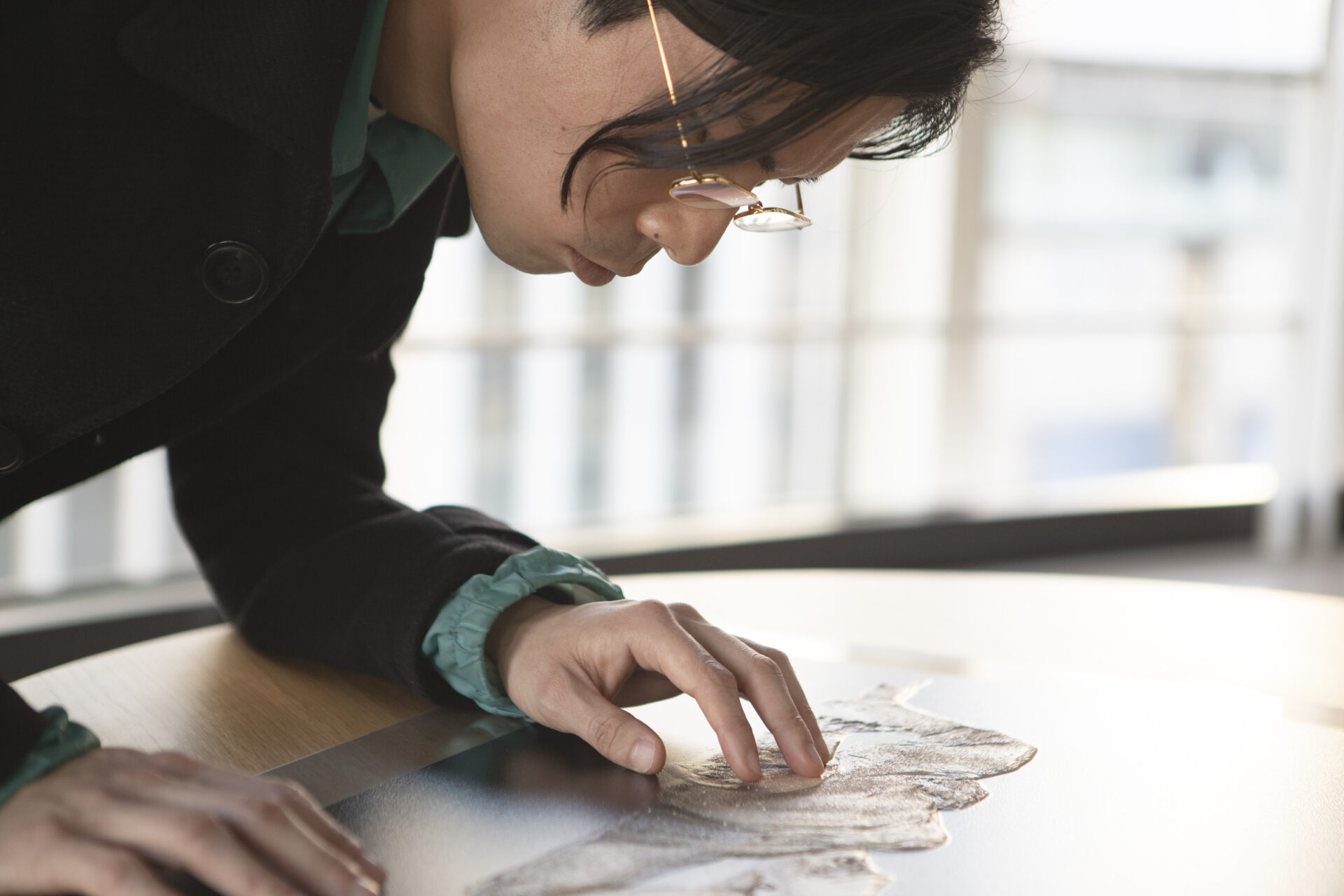

A sample of Kao1 and Yamauchi, who ‘sees as if he touches.’ This is a sculptural piece molded by vacuum forming into the shape of a face through StareReap2.5 printing.

A sample of Kao1 and Yamauchi, who ‘sees as if he touches.’ This is a sculptural piece molded by vacuum forming into the shape of a face through StareReap2.5 printing.

A sample of a StareReap2.5 print, depicting the gorilla from Maihime. “I want the audience to experience a slightly grotesque, but at the same time erotic, sensation of skin.”

A sample of a StareReap2.5 print, depicting the gorilla from Maihime. “I want the audience to experience a slightly grotesque, but at the same time erotic, sensation of skin.”

Shota Yamauchi

Born in 1992 in Gifu. Completed his post-graduate studies at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts, in 2016. His major exhibitions include ‘The Second Texture’ (Gallery TOH, 2021), ‘Ripple Across the Water 2021’ (WATARI-UM, The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, 2021), ‘The Museum in the Multi-layered World’ (NTT Inter Communication Center, 2021), and ‘Terrada Art Award 2021 Finalists Exhibition’ (Warehouse TERRADA G3-6F, 2021).

Born in 1992 in Gifu. Completed his post-graduate studies at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts, in 2016. His major exhibitions include ‘The Second Texture’ (Gallery TOH, 2021), ‘Ripple Across the Water 2021’ (WATARI-UM, The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, 2021), ‘The Museum in the Multi-layered World’ (NTT Inter Communication Center, 2021), and ‘Terrada Art Award 2021 Finalists Exhibition’ (Warehouse TERRADA G3-6F, 2021).

Shota Yamauchi

Born in 1992 in Gifu. Completed his post-graduate studies at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts, in 2016. His major exhibitions include ‘The Second Texture’ (Gallery TOH, 2021), ‘Ripple Across the Water 2021’ (WATARI-UM, The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, 2021), ‘The Museum in the Multi-layered World’ (NTT Inter Communication Center, 2021), and ‘Terrada Art Award 2021 Finalists Exhibition’ (Warehouse TERRADA G3-6F, 2021).

Born in 1992 in Gifu. Completed his post-graduate studies at the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts, in 2016. His major exhibitions include ‘The Second Texture’ (Gallery TOH, 2021), ‘Ripple Across the Water 2021’ (WATARI-UM, The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, 2021), ‘The Museum in the Multi-layered World’ (NTT Inter Communication Center, 2021), and ‘Terrada Art Award 2021 Finalists Exhibition’ (Warehouse TERRADA G3-6F, 2021).